Persons who step up to leadership tend to be motivated, smart, and sincere in their desire for success, for themselves and for the organization. Some leaders are go-getters who want to fix a system (and the people in it). They want to create a successful organization and will take on the challenge of "changing the system." When they've had success in a previous context they will tend to enter a challenging dysfunctional system with the confidence that they will be able to duplicate the successes made in one context in another. The liability here, of course, is the tendency to focus leadership on the personality of the leader and failing to take into account the reality that (1) not all systems are created equal, and (2) leadership is as much a function of the system as it is of the individual designated "leader" in the system.

The corrective to the perils of a personality-focused leadership is the appreciation that leadership is always contextual, and, context matters a lot. Not all systems are alike, though systems tend to be "of a kind." A biological family system is not the same as a congregational relationship system, even if the church is made up of families. A for-profit business is not the same as a non-profit organization, even when both provide the same service. A theological school is not a church community, even though both share similar beliefs and practices. Effective leaders understand that the function of leadership is as much (if not more) a product of the system than of the personality of the leader in the system. Therefore, leaders must understand the context and type of system they are in.

Two recent conversations with highly motivated but frustrated leaders underscored the importance of understanding one's system. Both are smart, experienced, and confident leaders. Both have had successes at former contexts in similar systems (one a non-profit organization and one in an congregational context). But both are very frustrated at the slow pace of change they are making helping their organizations succeed. Both express a feeling of being stuck and facing problems they are not able to "fix" for the first time. One said, "It feels like pushing against Jello around here." The other said, "At this point I'd settle for us just being a healthier place."

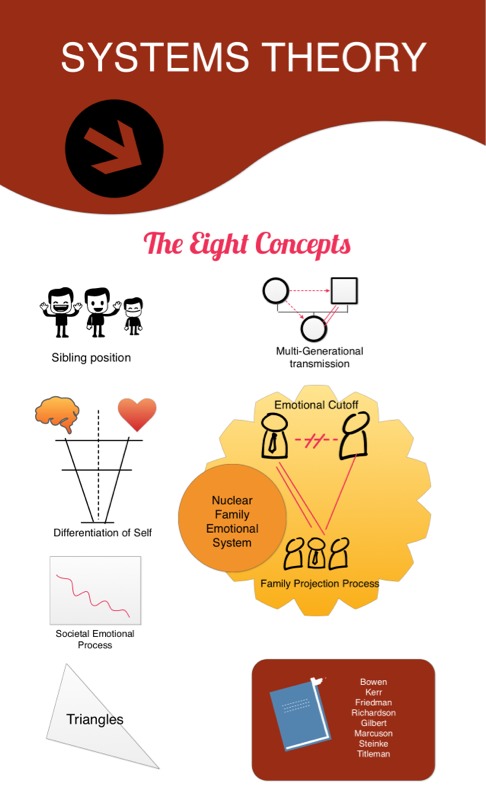

These leaders were facing the particular challenge of trying to lead chronically anxious systems. These types of systems are structured with chronic anxiety as an integral part of their homeostasis and patterns of emotional process. They come about when their structure: (1) makes someone in the system responsible for someone else's functioning, (2) has triangles as a patterned way for emotional processes, and (3) is designed so as to inhibit the effectiveness of the leader. At best, these systems lack the internal resources to improves, and, at worst, they are highly resistant to change and tend to have a perverse devotion to their dysfunction. Any leader with Messianic leanings will become prone to burnout in such systems.

Does this mean these leaders should just give up on their systems? No, I still think the presence of a mature and effective leader remains one of the most significant factors in helping a system function better, if not realize success. But it can help to adjust one's assumptions, perspectives, and functioning as leader in an chronically anxious system stuck in its dysfunction. The challenge for leaders in this context is to adjust their leadership functioning without accommodating to the system.

In what ways might high-performing leaders adjust their perspective, expectations and functioning in a chronically anxious system? Here are some ways:

Work at containing the toxins in the system to empower the strengths in the system. Toxic elements include those who sabotage efforts, become entrenched, gossip, are willful, act irresponsibly or act as terrorists in the system. These persons impede progress and keep the system stuck by holding others emotionally hostage, being a distraction, or actively undermine the efforts of others in the system. In chronically anxious systems that lack capacity for dealing with these persons, it is the leader who must provide appropriate intervention.

Invest in and release the high performers. As leaders contain the toxins in the system they will be able to release and empower the high performers in the system. Dealing with the toxic members of the system takes a lot of energy, but leaders should make it appear that they are investing more time and attention to the healthy and most motivated persons in the system. Give them the support and resources they need and soon they'll learn to take their cues from you, the leader, rather than from the naysayers and chicken-littles in the system.

Inculcate accountability. Chronically anxious systems tend to have developed a pattern of not holding persons accountable. This enables underfunctioners and underperformers to "set the tone" for the work ethic in the system. Leaders in this kind of system must address these unprofessional and irresponsible behaviors.

Be responsible for your office and your functioning. Balance with the above, leaders in dysfunctional systems do better in focusing on taking responsibility for their own functioning and responsibilities while not making themselves responsible for other people's functioning. It sounds paradoxical, but it appears universally true that to the extent a leader can do this, the system functions better.

Give up expectations of outcomes. "A leader can only accomplish what the system allows," claimed Edwin Friedman. Chronically anxious systems with high levels of dysfunction tend to lack the internal capacity to attain goals, realize vision and live into the mission of the organization. A leader who inflicts lofty goals and specific outcomes on this system is setting up him or herself, and the system, for disappointment and frustration. It is likely these systems need to focus on being "better" before they are able to focus on doing and producing "more." However, while the leader will do well to lower his or her personal expectations, it is appropriate to demand more of the system--the best people in the system will step up.

Gain clarity about your goals and your tenure in office. What do YOU want to accomplish in your tenure as a leader is a better orientation than what you want the system to accomplish. Remember that it is willfulness that brings out the toxicity in a system. Focus on your goals as a leader over any goals for the system.

Gain clarity about the function you serve in the system (the one you desire and the ones the system assigns to you). Entrenched and systems with rigidity in their emotional process tend to assign roles and functions to individuals in the system. Double so for leaders in chronically anxious systems. The roles, with accompanying functions are varied: rescuer, fixer, scapegoat, etc. Whether you like it or not, a chronically anxious system will assign you the role it expects of its leader based on rigidly patterned relationship structures. Leaders in these systems do not have to accept those roles and expectations, but should not be surprised about how they will continue to haunt them as long as they remain in the position or leader.

Build a narrative for success (vision, identity, values). Every system needs and craves direction from its leader; they want that "vision thing." Chronically anxious and dysfunctional systems tend to build a narrative of victimization and defeat over time. Leaders can "re-wire" the self perception and outlook of a system by creating a new narrative for the system. This can be done in many ways, from re-interpreting past crises, nodal events, and critical instances, to providing a narrative for the future of the system. Effective leaders tend to not underestimate the function of the leader as resident storyteller and interpreter of the systems' narrative because they know it is one way to shape its identity.

Leadership is a product of a system, more so than a function of one individual's personality, skills, or competence. As such, leaders do well to understand the nature of the system they lead and the context in which it resides. In this way, leaders can move toward being more effective by providing the leadership function the system actually needs through adaptation rather than accommodation.