Tuesday, July 29, 2014

The Five People You Need as a Leader

Monday, July 21, 2014

Six "Tells" of the Differentiated Leader

"Yes!" he said, "that's exactly where I'm at!"

We talked some more about his ideas. I found it an enriching conversation, and it sparked in me some thinking on the issue. Recently, someone else had asked me "How can leaders know if they are functioning in differentiated ways?" That's a great question given (1) the limitations of our own subjectivity; (2) our propensity for self-referencing; and (3) the challenge of Bowen Family Systems Theory to "stick to observable facts" when interpreting emotional process.

One common error is the misunderstanding of striving to "be a self-differentiated leader." That is, achieving some mythic state of being. Leaders will do better to focus on what Murray Bowen called the "functional level of differentiation." I think that means that the "tell" of a differentiated leader is more about one's capacity to function in context and relationships and less about an over-focus on some internal state of being arrived at through gnosis, expertise, or practices.

Here are six ways to"tell" one is functioning as a differentiated leader:

- Assess your pattern of functioning over time. Is there evidence of consistent self-regulation and effective functioning over a span of periods of high-anxiety, crises, stress, and times of relative calm?

- Assess your repertoire for responding to rather than reacting against anxious behaviors and situations. Do have have a wider range of responsive options than you did previously? Can you both act differently and think divergently?

- Assess to what extent and in what ways your functioning directly influences toward the better the functioning of people most closest to you.

- Assess your capacity to consistently take a more principled position and hold it against the opposition of important persons in the system. Do you function consistently out of your values than out of what is expedient?

- Assess the extent to which your functioning is increasingly mature and non-reactive in the face of stressors that used to trigger reactivity and poorer functioning.

- Assess the extent to which other people close to your leadership position exhibit higher levels of functioning and less reactivity (fewer cutoffs, less enmeshment, less seriousness, reduced gossip, less secrecy, etc.).

My new doctoral student friend thanked me for our conversation. He reported being encouraged and having some new ideas after our talk. I think he'll do well with what sounds like an interesting research project. I look forward to his research. I hope he'll discover additional evidences of a differentiated leader. I think we can always use a few more.

Israel Galindo is Associate Dean for Lifelong Learning at the Columbia Theological Seminary. Formerly, he was Dean at the Baptist Theological Seminary at Richmond. He is the author of the bestseller, The Hidden Lives of Congregations (Alban), Perspectives on Congregational Ministry (Educational Consultants), and A Family Genogram Workbook (Educational Consultants), with Elaine Boomer and Don Reagan. Galindo contributes to the Wabash Center's blog for theological school deans.

Friday, June 20, 2014

Marcuson's 111 Tips to Survive Music Ministry

Second to the congregational youth staff person, church musicians may be the most prone to be the focus of anxieties stemming from everything from tastes in styles, performance issues, aesthetic predilections, or systemic scapegoating.

Margaret Marcuson's new resource, 111 Tips to Survive Music Ministry, is a great help to those working in music ministry. The tips are "right on": common sense, intuitive, and practical. The tips are organized by categories: worship, relating to the pastor, music, leadership, learning, pastoral care, and five more.

The ebook is available from Creator for the special limited time introductory price of just $2.99. You can purchase it here.

Israel Galindo is Associate Dean for Lifelong Learning at the Columbia Theological Seminary. Formerly, he was Dean at the Baptist Theological Seminary at Richmond. He is the author of the bestseller, The Hidden Lives of Congregations (Alban), Perspectives on Congregational Ministry (Educational Consultants), and A Family Genogram Workbook (Educational Consultants), with Elaine Boomer and Don Reagan. Galindo contributes to the Wabash Center's blog for theological school deans.

Monday, June 9, 2014

Money and What it Represents Part 2: Approaching Stewardship Education As A Spiritual Issue

Stewardship is about a Christian’s personal, volitional response to God's call to discipleship as part of the Body of Christ. As such, stewardship is primarily a value (an individual, but also a corporate one), a practice (behavior) only secondly, and a concept or belief, thirdly. Given that framework, most congregations seem to tend to “teach” it backward and incompletely. Too often we attempt to teach Christian stewardship by using the teaching-by-telling approach and leaving it at that, never touching on the affective and the volitional and failing to facilitate the practice. Then, we naively expect that change will happen in the life of our members related to stewardship.

Stewardship is a Spiritual Issue

Stewardship is a spiritual issue, and it must be addressed like every other spiritual issue in the life of the believer. The issue is not to TELL people that they need to give 10% of their money to the church, rather, it is to help people arrive at a conviction of value by engaging them in the dialogue of theological reflection by asking, "Share with me, how are you responding to God in your stewardship of life?"

Our failure to help our members learn—--really learn-—-stewardship has had tragic results. Our unfortunate approach to teaching stewardship in the lives of our members means that we’ve done a great disservice to them over the years by being ineffective about helping them address the stewardship dimension of discipleship (except when it's time to ask for money for the church budget we tend to not even talk about it. And all evidence is that we’ve failed even there, since most members give only 2.3% of their income to the church).3 I suspect that we, the church leaders—pastors, teachers, deacons—have been irresponsible in helping our members in this, probably because we ourselves have not dealt with our own issues related to money.

In most of our churches, a significant number of our members are under the oppressive burden of debt, so much so that they are unable to respond in responsible stewardship to God. I suspect they resent us for it, because we've been of no help whatsoever to them in dealing with financial stewardship while making them feel guilty about not giving more money to the church. We've not been prophetic about challenging the values of the world our members have embraced and the myths of materialism the world teaches. So when we once or twice a year make our pitch for money, they can’t hear it, at least, they don't hear it theologically. And then there are the church members who have bought into the values of the world's materialism: how many people in your congregation spend more on feeding and caring for their pets than they do giving to the hunger offerings at church? How many spend more monthly on their cable TV and Internet service bill than they do to missions? How many church members spend more money on their annual vacation than they do giving money to help the homeless?

It's About Values

The issue of stewardship is complex because it less about the money and more about values. I think that we ought to address the issue of stewardship in the same way we address issues about faith development and discipleship: by taking into account developmental life stages and cycles. Different epochs in life require different messages about one’s response about stewardship of life. As a specific example: mid-life calls for a stewardship of generativity (learning to face the limitation of means and beginning to invest in the next generation. In effect, learning how to give your life away.). But that is not the case for adolescents and young adults whose life stage work appropriately includes acquiring and building. And how unfair, and nonsensical to its audience, are messages about stewardship of money to young children—who have no money and no cognitive concept of percentages or of proportional giving? And end-of-life stages, and stages of senescence, call for different ethical and theological decisions about stewardship. Only through dialogical engagement can people deal with these issues authentically in their lives. I suspect we make our messages of stewardship ineffective when we assume that it is the same for everyone at the same time, and we attempt to teach everyone the same way.

In terms of educational programming, not everything is for everybody at the same time. I think we confuse and make people feel uselessly guilty when we send the message that, regardless of their life stage, their family life cycle stage, and their particular life situation, they are supposed to function and respond like "everyone else." But rarely are they given the opportunity for learning through dialogue that leads to application, and therefore, I suspect most choose to make no legitimate response at all to God’s call in this area of their lives. Stewardship is as much a value and a choice as it is a concept and a practice. Unless we address all four domains of learning--knowledge, affect, behavior, and volition---our members will never “learn” stewardship.

Adapted from: How to Be the Best Christian Study Group Leader, by Israel Galindo (Judson Press)

To learn more about the course Money and Your Ministry, check out the Center for Lifelong Learning. Join us!

Israel Galindo is Associate Dean for Lifelong Learning at the Columbia Theological Seminary. Formerly, he was Dean at the Baptist Theological Seminary at Richmond. He is the author of the bestseller, The Hidden Lives of Congregations (Alban), Perspectives on Congregational Ministry (Educational Consultants), and A Family Genogram Workbook (Educational Consultants), with Elaine Boomer and Don Reagan. Galindo contributes to the Wabash Center's blog for theological school deans.

Wednesday, May 21, 2014

Money and What it Represents. Part 1

I am preparing for an online course on money and ministry to be taught in the fall with author Margaret Marcuson. Money, and what it represents is a complex issue in congregations. The course will examine money and ministry from a systems theory frame of reference. From that orientation, some systems concepts that can help in understanding what's going on are:

- Money represents something to people. Usually, it's emotional.

- Money often serves a function. Giving money represents a function of emotions, drives, or values.

- Since money is a complex emotional issue, it's helpful to never question motives, but observe function

- Stewardship is a spiritual-emotional issue and needs to be approached and understood as such.

Some time ago a colleague in ministry called to share good news, and, a concern. He was new to the church, only eight months into his new ministry. A relatively new member to the church (she had joined two years prior) had expressed how much she appreciated his ministry and the excitement he was bringing to the church. She gave him an envelope with a check in the amount of $5,000.00, "to be used any way you want for your ministry." My colleague was elated with the affirmation and the gift, but he felt a bit stuck, also. He was seeking counsel about why he felt conflicted about the gift.

When a new (recent) member to a congregation gives a $5,000.00 gift, red flags go up for me. I won't question motive, but I tend to ask questions about emotional functioning. A very FEW people can give large sums of money to a church with no emotional strings attached--but most people cannot, in my experience. Since a congregation is an emotional system--and since small congregations mimic "family" emotional systems--it is naive to think that money (and what it represents by way of its function) does not matter in terms of the impact on the function of the system.

In the case of a large donation from a new member, we may ask, for example:

- Is this person overfunctioning for the congregation?

- Is this person dealing with some issues in his or her life that has promted the gift? Why now?

- Does this person's (immediate) family know he or she is giving this gift? What is this persons relationship with the church? With the pastor?

- Did the pastor or staff get the gift or was it given to "the church" through usual giving channels?

- How does the giving of the major gift relate to patterns in the donor's life? In the church? In the pastor's family of origin?

- Are there guidelines in place (rules or policies) about "major gifts"? Were they followed?

- Does this action put you in a triangulated relationship?

- Were there "strings" attached to the gift? Overt or implied? Expectations? Subtle messages?

- Is the gift a "designated gift" for a ministry, staff person, pet program, pet issue that by-passes the regular budget? Is this gift given in stead or in lieu of regular offering and pledge giving?

- What are the systemic consequences to the congregation beyond convenience and financial relief?

- Given the donor's life circumstance, is this a "responsible" act? Is it appropriate?

- Given the pattern of giving and practice of stewardship of the congregation as a whole, is receiving the gift a responsible act? Is it appropriate?

- Will accepting this gift change or shift the relationship with the donor?

Events like my friend's experience are great opportunities to do some stewardship education with the church leadership. At least for pastoral leaders who are willing to put the issues on the table and challenge the church about its responsible response to congregational stewardship. Most pastors seem to avoid dealing with it and then wonder why their congregational members are poor stewards. Go figure.

NEXT: Money and What it Represents: Stewardship Education As A Spiritual Issue

Israel Galindo is Associate Dean for Lifelong Learning at the Columbia Theological Seminary. Formerly, he was Dean at the Baptist Theological Seminary at Richmond. He is the author of the bestseller, The Hidden Lives of Congregations (Alban), Perspectives on Congregational Ministry (Educational Consultants), and A Family Genogram Workbook (Educational Consultants), with Elaine Boomer and Don Reagan. Galindo contributes to the Wabash Center's blog for theological school deans.

Wednesday, May 7, 2014

Hacks and Professionals: Which are you?

I think that’s a challenging word to congregational leaders. It speaks to the dependency of so many leaders on fads and packaged programs that provide the promise of the quick fix for quelling the anxious voices who want to be entertained rather than challenged, who want to have “the answer” that satisfies rather than struggle with the questions that challenge, and, who cater to the whining voices of those who cannot tolerate being "bored" by engaging in the very practices and disciplines that lead to growth through the engagement of mind and affections.

The biggest liability for any system whose leader provides the quick fix is that it removes responsibility, denies accountability, and caters to the most anxious and dependent in the system. In the end these actions are inimical to the very processes and experiences that foster growth. In such a system there will never be growth and development toward maturity.

Being Transformed by Our Experience

For ministers and congregational leaders, a disciplined and sustained engagement in the practices of reflection-in-action and reflection-on-practice is what makes a difference in moving from novice to wisdom (or in Friedman's terms, from hack to professional). They guard leaders from being perpetually" blown here and there by every wind of teaching" and becoming distracted from the seemingly unrelated series of experiences day in and week out. Mature leaders are transformed by their experiences as a product of intentional reflection for meaning-making. They are lifelong learners who are inner directed, agents of their own learning, and who know that meaningful learning is more about the cultivation of insight than it is the acquisition of other people's knowledge.

Friedman’s words certainly challenge the congregational leader's own lack of personal and professional growth. I often tell search committees to value personal maturity over “experience.” Some people have years of “experience” but seem to have learned little from it.

Similarly, I witness too many resident congregational educators who seem to spend their careers running a Sunday School or other programs as the end-all and be-all to what constitutes Christian education. Too many seem to not have been transformed by the very discipline they are engaged in: education. For example, too few congregational educators seem able to articulate a well-defined philosophy of education that informs the basic educational questions:

- What constitutes learning?

- To what end are we educating?

- What is the nature and role of the teacher?

- What is the nature and role of the learner?

- What criteria do we use to discern what is worth learning from what is trivia?

- What does it mean to educate in faith?

- How do people actually learn, and therefore, how should we teach them?

- Kathleen McAlpin, Ministry that Transforms.

- Howard W. Stone, How to Think Theologically

- Donald Schon, The Reflective Practitioner

- Leadership in Ministry Workshops.

- Etienne Wenger, Communities of Practice.

Resources and Practices

Here are some resources for becoming a reflective practitioner:

Israel Galindo is Associate Dean for Lifelong Learning at the Columbia Theological Seminary. Formerly, he was Dean at the Baptist Theological Seminary at Richmond. He is the author of the bestseller, The Hidden Lives of Congregations (Alban), Perspectives on Congregational Ministry (Educational Consultants), and A Family Genogram Workbook (Educational Consultants), with Elaine Boomer and Don Reagan. Galindo contributes to the Wabash Center's blog for theological school deans.

Friday, April 25, 2014

Do You Make these 7 Leadership Mistakes When Dealing with Conflict?

After struggling for eight months and not getting anywhere, Victor starting seeking help in understanding what was going on and what to do about it. To his credit, Victor was also seeking to understand his own functioning in the midst of conflict. He started to recognize long-seated patterns in how he responded to the difficult experience at his church. It did not take long for Victor to name seven mistakes he was making in how he was dealing with conflict. Victor actually wrote down the list of the seven mistakes he was making and worked hard at consciously changing the way he was behaving.

Monday, April 7, 2014

Why are all systems so alike?

We hear hints about this apparent truth here and there. “Business is business, whether you’re manufacturing cogs, selling widgets, or selling a service.” I’ve been in certain leadership training seminars where the room held representatives from all manner of contexts, with corporate CEOs to clergy attending to the same latest ideas about how to lead better and manage more effectively in their organizations.

I have some hunches as to why all systems are so similar:

Relationships systems follow universal rules. I first stumbled across this insight when I picked up a book titled How to Run Any Organization. I still have in on my bookshelf, and I must admit it has served me well in all the contexts I’ve worked in: school administration, corporate, congregation, non-profits, etc. The second place where that idea finds support is in Bowen Systems Theory, which identified universal rules applicable to all relationship systems, from family to business; from government to church. Because relationship systems self-organize according to universal principles, we can expect to see certain characteristics that are shared universally. These include: the function of leadership, the presence of anxiety and the manifestation of reactivity, the emergence of homeostatic dynamics, the presence of reciprocal dynamics (overfunctioning-underfunctioning, seperateness-togetherness, etc.), the emergence of systemic patterns that serve a variety of purposes.

Systems of a kind will tend to share the same organizational metrics as indicators of effectiveness, vitality, and viability. The metrics for "educational effectiveness" published by educational institutions--whether universities or theological schools--are similar, if not identical. The metrics used by non-profit organizations (e.g., those related to social value, market potential, and sustainability) apply to organizations of that kind regardless of size, mission, or location. While that makes common sense, what is surprising is how many leaders and board members of those organizations would not be able to identify those metrics if asked.

Complexity emerges from simple rules. While systems and organizations may appear different on the surface they seem all to arise and operation on fundamentally simple rules. The most complex corporation started small and is effective to the extent it can “follow the rules” of its nature. Large congregations look different from small congregations, but ask any pastor and he or she will likely confirm that no matter the size of the congregation, leaders tend to deal with the same problems. A large theological school looks different from a small seminary, but a room full of deans from schools across the spectrum of denominations, geographical areas, and school size will all share about the same challenges. And, they'll immediately chuckle at the comment, "We all have the same Faculty."

Human nature is the same everywhere. Culture, race, ethnicity, and epochs mediate the universal principles that direct relationship systems, but it doesn’t take much to scratch below the surface and discover that human nature is the same everywhere, and it has been for a long while. Perhaps the best place to see this is in narrative-—those stories that are so good about depicting the human spirit and its interior world. Reading the works of the Greek poets and playwrights to Shakespeare, to Checkoff and Dostoevsky to Mark Twain will serve to confirm that we humans laugh, cry, yearn, fear, and hope for the same things—-and always have. Idealists who want to create utopias and social organizations that are “totally new” often forget that those new creations will always be populated by the same old people.

The brain is the same everywhere. There may be a biological cause as to why all systems seem so similar. The organic brain, its patterns and its epistemology, are universally the same for everyone everywhere in whatever culture. Hence the educational truism, “Everybody everywhere learns the same way.” For example, barring neurological anomalies or organic brain syndromes, every person’s brain learns language the same way. And, dismissing claims of clairvoyance and ESP, everybody’s brain processes phenomenon the same way, for the most part. Given that fact, we can expect that when a group of individuals gathers together to form Group A, they’re pretty much going to be more similar than different to the group of individuals that gather together for form Group B. That’s a great convenience to teachers who find they can effectively re-cycle a well-designed courses year after year with little change and still achieve desired learning outcomes with little variance from the norm. This insight can help ease the transition for leaders moving from one context to another is a system of a kind (from one congregation to another, from one theological school to another). Culture and context will mediate some things--like emotional process, practices, ethos, and values--but all systems of a kind tend to function in much the same ways.

What are some of your hunches as to why systems are so similar?

Israel Galindo is Associate Dean for Lifelong Learning at the Columbia Theological Seminary. Formerly, he was Dean at the Baptist Theological Seminary at Richmond. He is the author of the bestseller, The Hidden Lives of Congregations (Alban), Perspectives on Congregational Ministry (Educational Consultants), and A Family Genogram Workbook (Educational Consultants), with Elaine Boomer and Don Reagan. Galindo contributes to the Wabash Center's blog for theological school deans.

Thursday, March 27, 2014

Five Essential Functions of Effective Leaders

Monday, March 17, 2014

Truisms worth remembering during times of acute anxiety

Tuesday, February 25, 2014

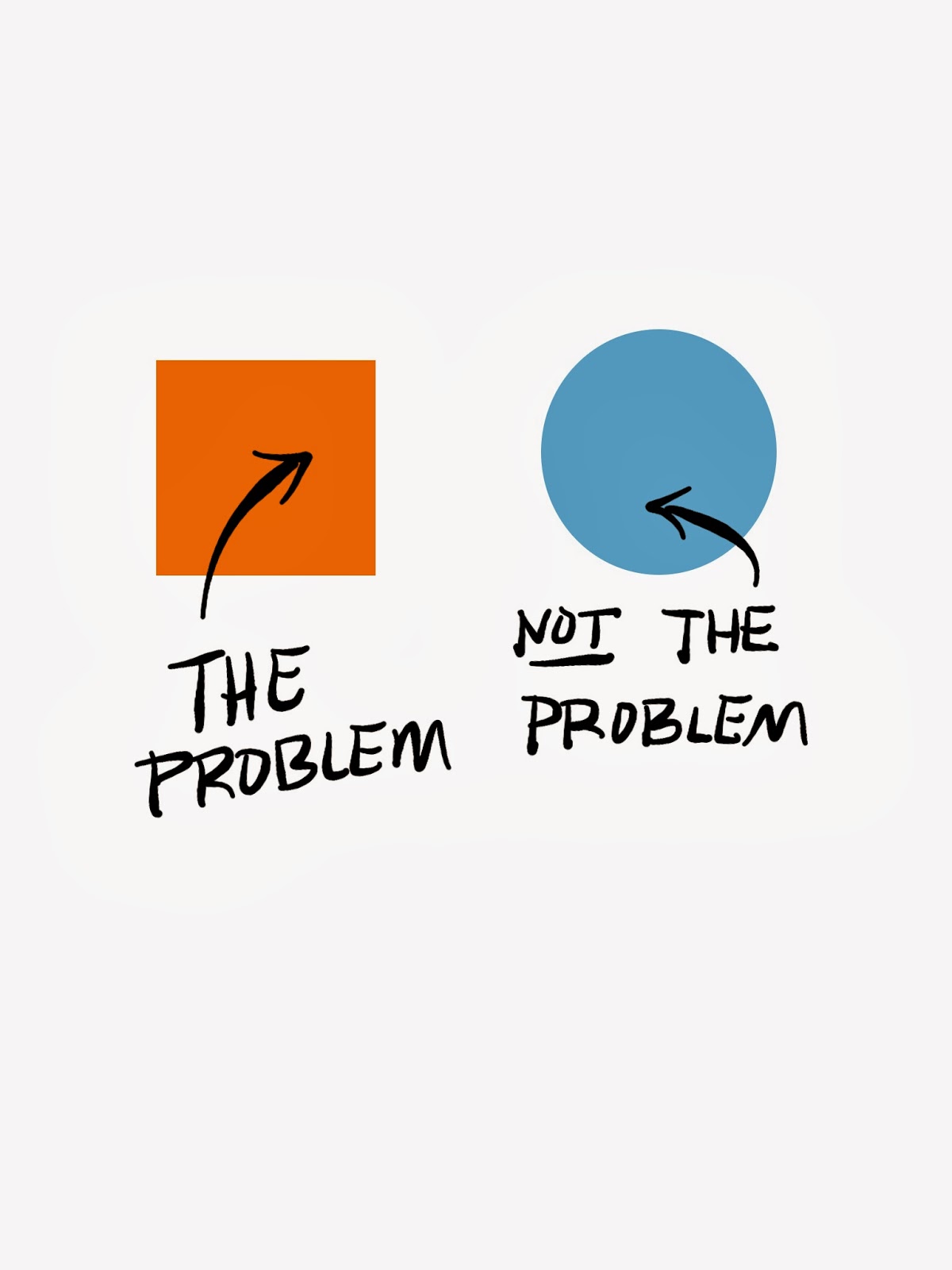

Fixing the Right Thing

- What is going on here, really?

- Can I identify the triangle?

- Do I need to accept the invitation into a triangle?

- Am I responsible for alleviating another person’s frustration, discomfort, or anxiety?

- Am I being asked to take responsibility for someone else’s behavior?

- Do we want to try to fix a person or fix a problem?

Thursday, February 20, 2014

Six responses of well-differentiated leaders

- Monitoring their own internal emotional process. Differentiated leaders are self-aware of the experience of their feelings, of how anxiety is being processed physically and emotionally, and awareness of the role family of origin dynamics are coming into play in the situation.

- Observing their functioning. Differentiated leaders are centered, clear, and responsive (emotionally present). They know the cues for when reactivity patterns start kicking in. For example, overfunctioning or underfunctioning at work and at home, obsessing over issues, fantasizing, or distancing.

- Regulating their anxiety. If reactivity patterns begin to manifest (e.g., psychosomatic symptomology), differentiated leaders work on regulating the experience of anxiety and moderate reactivity patterns.

- Avoiding reactivity. No matter how much they want to, differentiated leaders don’t call that acting out deacon a jerk or tender their resignation letter when frustrated.

- Getting clarity about their guiding principles and values. Differentiated leaders recall and rehearse their values, goals, principles, and vision (“Remind me again, why did I take this job?”).

- Seeking out resources. Differentiated leaders are not afraid of asking for help. They avail themselves of their coach or therapist, a spiritual friend, or support group. They don't seek advice about what to do or how to think, but use these resources to navigate through the emotional process in the midst of crises, acute anxiety, or reactivity.

- Those who have the capacity will be able to self-regulate and also begin to self-differentiate. That deacon you wanted to call a jerk may now be saying, “Wow, I don’t know what happened to me. I got caught up in something and went crazy for a moment there.” These people are now resources for you and the system.

- A second group of persons will tend to fuse with you. A self-differentiated leader is “attractive,” even to those who lack a capacity for self-definition. Fusion can be seductive. It feels great to have a room full of people nod at your every word and eagerly agree with your every opinion. However, this group of people are not a resource to the system—the next loudest voice can just as easily redirect their passions.

- The third group of persons will be the ones who will withdraw or cut off from you. Clarity about one’s stance will feel like a line drawn on the sand to some folks. Self-definition demands a response and responsibility on the part of others. For those who lack resilience in thinking, or who are too insecure or too rigid in their beliefs, cutting off may be their only repertoire for dealing with challenge.

Monday, February 17, 2014

Don't do these 10 things when dealing with reactivity

- Confront it head on. Taking on reactivity head on rarely is an effective tactic. For one thing we will find ourselves addressing the reactivity rather than its cause. A frontal assault on reactivity is merely reactivity to reactivity.

- Maintain an unreasonable faith in reasonableness. Persons caught in the grips reactivity are immune to data, or reasonableness. They are operating out of perceived threat, so their instincts have taken over the rational part of their brain. Allow time for the feeling of threat to pass before attempting a meeting of minds. There will be those who refuse to be reasonable for a number of reasons. The rules are different when dealing with those who refuse to reason.

- Question or ascribe motive to poor behavior. Because reactivity is a product of by-passing cognition it's not helpful to question people's motives. They are, literally, not in their right mind. Realize that people in acting out their reactivity are not at their best and are not acting out of principled thinking. Most likely, persons caught in the grip of reactivity don't know why they are acting the way they are.

- Take it personally. Ninety-eight percent of the time, the reactivity that comes your way is not about you, even when it feels like it. Occupying the leader position means you're the point person for reactivity, it comes with the job. Some reactivity will be projection of other people's issues, perceptions, or unresolved conflicts. Some will come your way just because it's convenient to dump it on your desk. Some will come to your just because people are feeling powerless and need someone to "do something" about it.

- Make it personal. Being on the receiving end of reactivity comes with the job. Often you'll be surprised at who vents frustration on you. Others will engage in a pattern of reactivity with you as the focus. Either way, focusing on the emotional process (people's functioning in the system) rather than focusing on the person, or personality, will help you get to the cause behind the reactivity. Personal attacks not withstanding, leaders do well not to take systemic problems worse by making it personal.

- Neglect to assess your part of it. There are fives sides to every story, and three you'll never find out about. There will be occasions when the reactivity (and accusations) leveled at you will, to some degree, actually be "about you." Our tendency will be to deny culpability, deflect blame, made excuses, avoid the discomfort of the situation, or simply convince ourselves we are not part of the problem. Mature and effective leaders have capacity to self-assess honestly their roles in systemic problems, and they are able to sincerely apologize and work at doing better.

- Forget to breath. When faced with reactivity we experience threat, and the biological response to it (fight or flight). Give your brain the oxygen it needs to think and reason--it's your most important resource in the midst of reactivity. So, breathe!

- Neglect to step back. Whether physically or emotionally, taking a step back from reactivity provides perspective. Taking a step back physically from a person engaged in reactivity helps remove a sense of psychological threat. Thinking to oneself, "Will this matter six months from now," can provide emotional distance and offer perspective to the existentially painful moment.

- Let your feelings rule over your principles. Informed values and principles are the two resources that provide correctives in the midst of reactivity. What values guide your relationship with persons--in whatever circumstance? What is your guiding principle when dealing with reactivity?

- Forget your place. You are the leader in the system, and you can't forget that. One of the burdens of leadership is that those in leadership do not have the luxury of giving in to the baser emotions. Getting angry, feeling outraged, nurturing feelings of victim-hood, holding a grudge, and lashing out may be emotionally cathartic, but once a leader gives in to them he or she ceases to be the leader in the system. When others in the system are loosing control of their emotions, that's the time a system needs its leader to be the most centered, non-reactive, and principled person in the system.

Tuesday, February 11, 2014

The Fascinating Power of Homeostasis

Wednesday, January 29, 2014

When it's not about you, but it involves you

Tuesday, January 21, 2014

10 leadership Commandments for Clergy

- Thou shalt not make thyself dependent on the Church for your salvation, for she is not your God.

- Thou shalt cultivate your relationship with your family of origin, for it is your once and future hope.

- Thou shalt not sacrifice your family and its members for the sake of ministry, for they are your first ministry.

- Thou shalt not accommodate to weakness, neither in yourself or in others. For fear, timidity, insecurity, and neediness are a lack of faith.

- Thou shalt not create the congregation in your image, for that is willfulness and a form of idolatry.

- Thou shalt practice courage and persistence of vision in the face of opposition, for a system needs its leader.

- Thou shalt invest in other people's growth---your staff, your employees, your congregational members--for that is an aid to differentiation.

- Thou shalt master triangles, for they shall be with you till the end of time.

- Thou shalt practice responsible stewardship of your calling. Invest in your own growth and development: personal, spiritual, emotional, physical, mental, and professional, for a church can only be as healthy as its leader.

- Thou shalt embrace imagination and adventure, for they will get you farther along on the journey.

Thursday, January 16, 2014

10 Leadership Quotes from Edwin Friedman

1. “The colossal misunderstanding of our time is the assumption that insight will work with people who are unmotivated to change. Communication does not depend on syntax, or eloquence, or rhetoric, or articulation but on the emotional context in which the message is being heard. People can only hear you when they are moving toward you, and they are not likely to when your words are pursuing them. Even the choicest words lose their power when they are used to overpower. Attitudes are the real figures of speech.”

2. "Leadership can be thought of as a capacity to define oneself to others in a way that clarifies and expands a vision of the future."

3. "The colossal misunderstanding of our time is the assumption that insight will work with people who are unmotivated to change."

4. "In any type of institution whatsoever, when a self-directed, imaginative, energetic, or creative member is being consistently frustrated and sabotaged rather than encouraged and supported, what will turn out to be true one hundred percent of the time, regardless of whether the disrupters are supervisors, subordinates, or peers, is that the person at the very top of that institution is a peace-monger."

5. Leaders need "... to focus first on their own integrity and on the nature of their own presence rather than through techniques for manipulating or motivating others."

6. "Sabotage . . . comes with the territory of leading.... And a leader's capacity to recognize sabotage for what it is---that is, a systemic phenomenon connected to the shifting balances in the emotional processes of a relationship system and not to the institution's specific issues, makeup, or goals---is the key to the kingdom."

7. "...leadership is essentially an emotional process rather than a cognitive phenomenon..."

8. "...'no good deed goes unpunished'; chronic criticism is, if anything, often a sign that the leader is functioning better! Vision is not enough."

9. "Living with crisis is a major part of leaders' lives. The crises come in two major varieties: (1) those that are not of their making but are imposed on them from outside or within the system; and (2) those that are actually triggered by the leaders through doing precisely what they should be doing."

10. "..the risk-averse are rarely emboldened by data."

Sources: A Failure of Nerve: Leadership in the Age of the Quick Fix (Seabury Books, 2007); Generation to Generation: Family Process in Church and Synagogue (The Guilford Press, 1985).

Israel Galindo is Associate Dean for Lifelong Learning at the Columbia Theological Seminary. Formerly, he was Dean at the Baptist Theological Seminary at Richmond. He is the author of the bestseller, The Hidden Lives of Congregations (Alban), Perspectives on Congregational Ministry (Educational Consultants), and A Family Genogram Workbook (Educational Consultants), with Elaine Boomer and Don Reagan. Galindo also contributes to the Wabash Center's blog for theological school deans.