Once, a colleague at work stopped by my office to review a communication glitch he was having with a staff person I supervised. The nature of the staff person’s work interfaced with my colleague’s office, but they’d had a history of finding it difficult to work together.

I listened to my colleague for about five minutes as he talked about the staff person, Susan (not her real name), and the problem. I noted that the focus of the content of his talk was Susan (her personality, behavior, etc.), and only peripherally did he identify what the problem was. I discerned that, once again, these two persons were stuck and I was being invited into an anxiety triangle.

Fortunately, my colleague is an emotionally mature person and we have a good working relationship. A student of systems theory, my colleague is a relatively level-headed, non-anxious person. But like many of us, some persons seem to push a reactivity button within him. When Susan pushed my colleague’s reactivity button, the resulting anxiety caused him to triangle someone into the matter, and I was in the position to be the natural candidate. Given our open working relationship I was confident in challenging him on how to approach the situation.

When he finally finished sharing a list of complaints about the staff person in question I asked him, “Can I ask you a systems question?”

“Yes,” he said, now on alert.

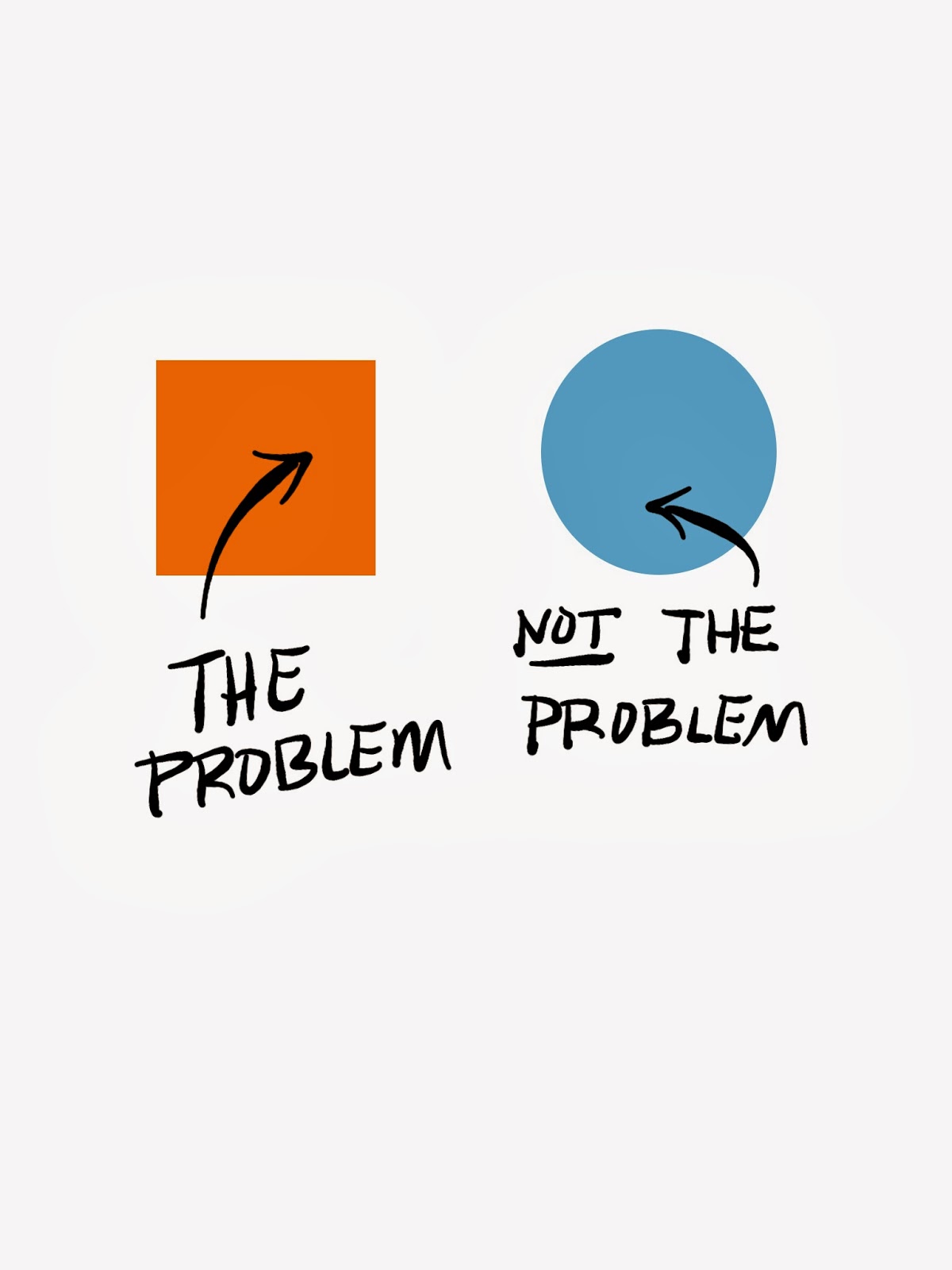

“Are you trying to fix Susan or are you trying to fix the problem?” I asked.

My colleague immediately recognized the emotional process at play. He realized that his reactivity was causing him to overfocus on Susan, and that he was triangling me into the situation by hinting that, as her supervisor, I needed to “fix” Susan. With that insight, we were able to shift the conversation from Susan to identifying what the problem was that needed to be fixed, in this case, clarifying a procedural matter between two offices.

Reactivity often manifests itself in anxious behaviors: an overfocus on personalities, a misdirection of an issue, projection, triangling someone into the unresolved issues between two persons, scapegoating, etc. Because I was able to regulate my own anxiety in the midst of the meeting, I was able to ask myself “What’s really going on here? What’s the issue?” I was able to help my colleague re-frame the problem. He was also able to get in touch with his own reactivity and realized how it was manifesting itself in triangling me into the matter by asking me to take responsibility for another person’s behavior and asking me to “fix” that person.

If I had been unfocused that day, things may have gone differently. I may have gotten caught up in the anxiety and reactivity, accepted the invitation to enter the triangle, made Susan the IP (Identified Patient), and my colleague and I could have launched into a futile project of trying to “fix Susan.” Furthermore, the real problem needing attention would have gone unresolved, which would serve only to increase the frustration and anxiety.

When faced with reactivity it is helpful to monitor one’s anxiety and cerebrate rather than ventilate by asking oneself questions of discernment:

- What is going on here, really?

- Can I identify the triangle?

- Do I need to accept the invitation into a triangle?

- Am I responsible for alleviating another person’s frustration, discomfort, or anxiety?

- Am I being asked to take responsibility for someone else’s behavior?

- Do we want to try to fix a person or fix a problem?

Israel Galindo is Associate Dean for Lifelong Learning at the Columbia Theological Seminary. Formerly, he was Dean at the Baptist Theological Seminary at Richmond. He is the author of the bestseller, The Hidden Lives of Congregations (Alban), Perspectives on Congregational Ministry (Educational Consultants), and A Family Genogram Workbook (Educational Consultants), with Elaine Boomer and Don Reagan. Galindo contributes to the Wabash Center's blog for theological school deans.